I’m an avid consumer of queer media. This year my favourite film has been Theatre Camp (2024), and last was I Saw the TV Glow (2024). Camp is my favourite genre by far, but I do love an indie reflective film too, despite their heaviness.

After watching Aftersun (2022), I did what I always do: I followed the emotional damage back to the source, Paul Mascal. I tried getting into Normal People (never happened), and I added All of Us Strangers to my watchlist. And listen, the watchlist might be a dungeon curse at this stage of media consumerism. Once I click “save,” it’s like the film disappears into a digital purgatory where art goes to die.

But then I was on a flight to Hong Kong and All of Us Strangers was right there on the in-flight catalogue. I started watching it, but didn’t finish it. Maybe the intensity of that bath scene wasn’t appropriate for an open space. Maybe the film was too heavy for my nervous system to take in all at once. Either way, I had to split it into two sessions.

The ending landed like a quiet collapse.

Spoilers ahead.

And yet, I didn’t write about it. Until last year, when I was studying Freud’s concept of the uncanny.

What’s the correlation between queer grief cinema and a 1919 psychoanalytic essay? If you’ve read more than one thing I’ve written, you already know the answer: I connect dots on anything that gives me even a single strand to pull.

This post will stand out as more academically written than others due to the topic at hand, but I hope my academic tone can still entertain you. Our topic at hand is: how All of Us Strangers (2023) reconfigures the uncanny into a contemporary interpretation of mourning and belonging.

This post engages with a few concepts from psychoanalysis and cultural theory. You don’t need prior knowledge to follow along, but here’s a brief grounding for anyone unfamiliar with the terms I’m using:

Hauntology (Derrida): describes experiences that are neither fully absent nor fully present, such as ghosts, memories, or unresolved grief.

Ontological: relating to the nature of being or existence. In this context, it refers to whether the ghosts are “real,” imagined, symbolic, or something in between.

Liminal: something that exists in-between categories, moments, or identities, neither fully one thing nor another.

With that in mind, here we go.

The Architectural Uncanny

In popular culture, the uncanny is often used to describe distorted human likenesses in digital media, or the unsettling atmosphere of haunted houses and ghost stories. Yet its origins are more complex. In his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche, Freud theorised the uncanny as a disturbance of boundaries between binaries. For Freud, the uncanny emerges when something once familiar and intimate returns in an altered, estranged form. The uncanny is therefore rooted in repression and repetition, when what is known but denied resurfaces. In visual storytelling, the uncanny often manifests spatially, through spaces that appear homely but threatening.

It is within this framework that Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers can be read. The film’s opening scenes situate Adam in a sterile, glass-walled apartment complex on the outskirts of London, a space that is meant to be domestic yet feels lifeless. Drawing on Vidler’s 1992 concept of the architectural uncanny, these modernist interiors reflect Freud’s idea of the unhomely: the home as both refuge and alienation. The reflective surfaces and transparent walls create an atmosphere of exposure rather than intimacy, turning private life into a spectacle, with ourselves as the audience.

The city’s empty streets, glass towers, and distant skylines evoke spectrality, as if depopulated by grief. The film’s colour palette: muted greys, soft yellows, and half-light; reinforces the sense of time suspended. Adam’s haunting is therefore not only psychological but spatial: an expression of contemporary loneliness embedded within the architecture of late capitalism.

Haunting or Hallucination?

Haigh’s direction deliberately blurs the line between haunting and hallucination, reframing the supernatural as psychological projection. The apartment mirrors Adam’s internal emptiness. As Avery Gordon (2008) argues, haunting is “a constituent element of modern social life,” a way in which unresolved emotional and social absences make themselves felt. Adam’s encounters with his parents illustrate this: the ghosts do not break reality but instead reveal its hidden fears and pain.

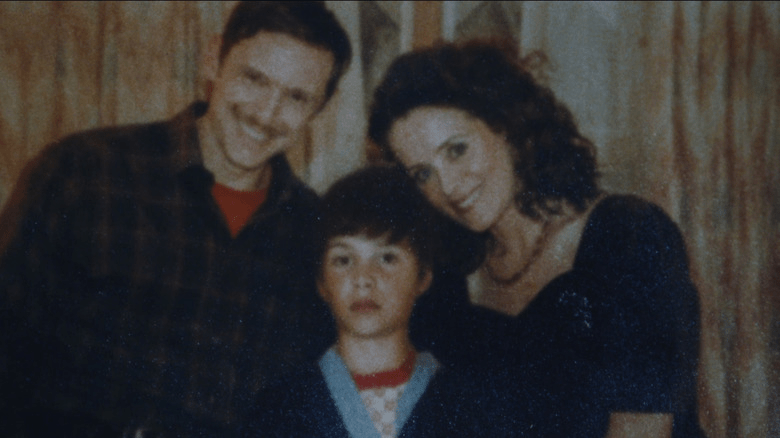

In Haigh’s film, temporal collapse is constant: Adam’s childhood home appears unchanged, and his parents remain ageless. Time itself becomes haunted, and the viewer, like Adam, is caught in a cycle of repetition that never fully resolves.

This ambiguity extends to the viewer’s perception. The film never confirms whether these encounters are paranormal phenomena, symbolic manifestations of grief, or cinematic delusions. This uncertainty situates the audience in a position of compliance with scepticism.

An important scene in All of Us Strangers occurs when Harry, Adam’s lover, glimpses Adam’s parents through the glass under the influence of MDMA. This moment destabilises certainty. If Harry can see them, are the ghosts real, or has Adam’s delusion expanded into a shared hallucination? The film situates perception itself as unreliable. The shared vision of the ghosts could be read as a collective hallucination, but the drug’s presence also complicates the ontological status of the apparitions.

Harry’s subsequent death transforms this ambiguity into tragedy, implying that intimacy with the supernatural, or with unresolved grief, can be fatal to those already emotionally fragile.

Emotional Haunting and the Uncanny

All of Us Strangers is structured through uncanny doubling: parents who return as idealised yet impossible versions of themselves, and Harry, who becomes both lover and ghost. What once served as a defence returns as something terrifying. In Adam’s case, each figure he encounters mirrors a different form of loss, offering comfort while simultaneously disturbing him.

Adam’s parents are the familiar objects of his earliest attachments, yet their return violates the natural order. The childhood grief Adam never resolved resurfaces in embodied form. The ghosts serve as mirrors of the unresolved past.

Harry functions as a second axis of uncanny doubling. His relationship with Adam unfolds in a way that already feels ghostly: he appears suddenly, moves quietly in and out of Adam’s life, and remains emotionally distant. When Harry is later revealed to have died before their final encounter, he becomes a spectral lover. This narrative twist produces a distinctly modern form of the uncanny, where romantic intimacy becomes inseparable from haunting. The person Adam loves is both alive and dead, present and lost.

In this sense, the uncanny does not reside solely in the ghosts of Adam’s parents, but in Adam’s struggle to form meaningful connections while carrying unresolved grief. The ghosts represent not supernatural horror, but the emotional labour of mourning itself.

The film’s final sequence brings this emotional uncanny into focus. Adam lies beside Harry’s dead body in the apartment and chooses to remain within the spectral realm rather than return fully to the world of the living. His decision suggests an acceptance that haunting is now central to his identity. Adam’s acceptance of the ghosts signifies the recognition that grief is not an interruption of life, but an ongoing condition.

Unlike many Western ghost narratives, which are clearly framed as horror, thriller, or supernatural mystery, All of Us Strangers occupies a liminal genre space. Marketed primarily as a psychological drama centred on queer loneliness and human connection, the film initially appears to disavow the supernatural altogether. Yet the presence of ghosts quietly disrupts this framing, sustaining an ambiguity rarely found in mainstream depictions of the paranormal. The film shifts attention away from the ontology of ghosts and toward the ontology of grief itself.

By refusing to resolve its ambiguity, All of Us Strangers frames the uncanny as a condition of living with loss: a quiet, intimate haunting that persists.

References:

- Freud, S. (1919). Das Unheimliche [The Uncanny].

- Vidler, A. (1992). The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. MIT Press.

- Gordon, A. (2008). Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota Press.

- Derrida, J. (1994). Specters of Marx. Routledge.