I came across The Crescent Moon with Cats or Mizuki to Neko while travelling back home to Spain to visit my sister. We aren’t blood-related, more like foster sisters, but she’s my family all the same. I clicked on the film because I saw cats in the thumbnail (as expected of a cat lady in the making like me) anticipating something light to watch on the way, a cute and soft slice of life a la Japanese. Instead, I found a story about found family, just as I was on my way to visit my own.

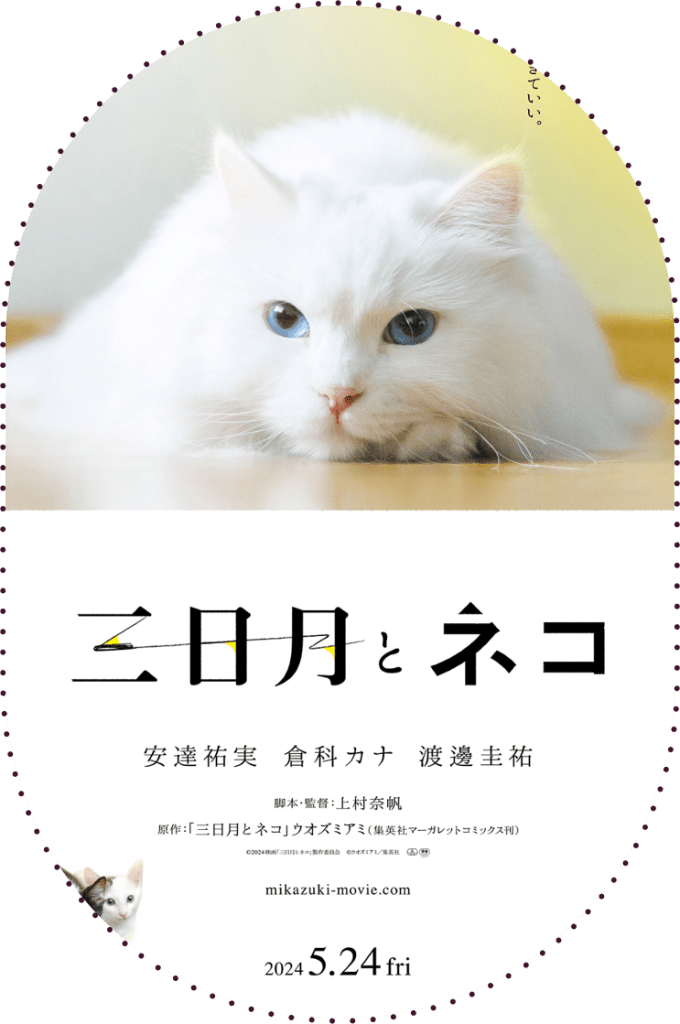

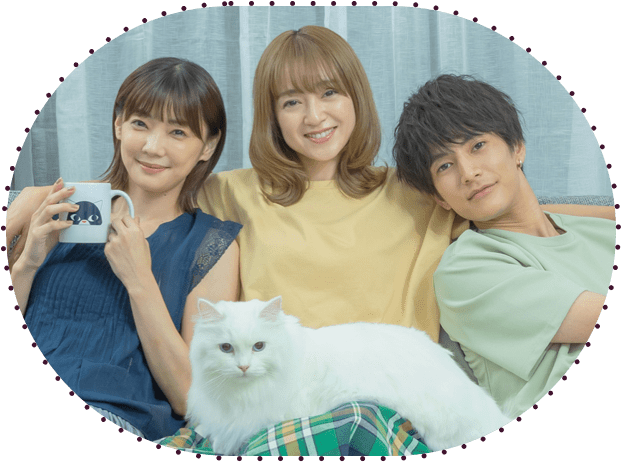

Directed by Kamimura Naho and based on Uozumi Ami’s 2019 manga, The Crescent Moon with Cats (2024) follows Akari, a forty-year-old woman who evacuates with her cat during an earthquake. On her journey she meets Kanoko, another evacuee in her thirties, and Jin, a younger man in his twenties from their building who also has a cat. What begins as coincidence soon becomes companionship. Through shared routines and quiet understanding, they build a home together.

The cats are central to the film’s narrative. At first, they act as emotional companions for their owners, but as the characters move in together, the animals take on a deeper role, almost representing children within the household. They create a sense of shared purpose, of something to care for together. Howell (2007) writes that kinship and community can often be imagined and built beyond blood ties, formed through shared care and daily life. The film illustrates this perfectly. Love is not declared; it is shown through feeding, cleaning, and the small, unspoken rituals that make a house feel like home.

Living together begins as a practical decision. Sharing bills and responsibilities makes sense in this difficult economy, but it quickly grows into something much more intimate. Akari loves cooking for the people she loves, and her joy in preparing food becomes a small act of devotion to the new household. Their evenings are marked by simple comforts, eating together, watching films, and coexisting in a quiet space of mutual safety. This emotional security is as important as the physical one, especially in an environment marked by natural disasters.

Nonetheless, their peace is limited by external social expectations. The pressure begins with Akari’s mother, who warns her that her younger roommates will soon leave her behind, that she needs to marry before she’s truly alone. When Akari meets a man who seems kind and stable, she feels both lucky and terrified. She likes him, and she knows that moving in with him would make sense if she wants to keep him, yet something in her resists. She doesn’t want to leave the home she has built, but the lack of visible attachment from her housemates makes her doubt her place there. When they congratulate her on the relationship, it feels polite. She realises that the space where she wanted to feel most needed might not need her at all. This echoes the sentiment of the so-called “old cat lady”, and fittingly, Akari is a librarian, perfectly matching that stereotype. She embodies how society pressures women into relationships out of the imaginary feminine fear of being alone, a fear treated as a flaw one must fix. Meanwhile, the “male loneliness epidemic” is often framed as a societal crisis requiring collective attention. Both are equally harmful and born from the same systemic roots, merely shaped by gender norms in opposite directions. Both deserve compassion and change, but I digress.

This quiet ache becomes the emotional core of the film. When the time comes for Akari to leave, both she and her housemates must confront what their bond truly means. What they have built together might not fit the conventional image of family, but it holds the same sense of loyalty, care, and belonging.

SPOILERS AHEAD: Akari ultimately chooses to stay, keeping her long-distance relationship but refusing to abandon the home she has created. The final moments show Jin returning from Tokyo after some years of work travelling, reaffirming that family is not something we inherit, it is something we build, and something that waits for us to come back.

As the film closes, it echoes the idea that “the bond that links your true family is not one of blood, but of respect and joy in each other’s life” (Bach, 1977) with a cozy scene between the found family and close friends. It is a quiet reminder that love is not limited by convention, and that connection, whether human or feline, can become a foundation strong enough to call home.

REFERENCE:

Bach, R. (1977) Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah. New York: Dell Publishing.

Howell, S. (2007) ‘Imagined kin, place and community: Some paradoxes in the transnational movement of children in adoption’, Social Anthropology, 15(2), pp. 135–151.