If this discussion is about “Alice and Fashion,” it is inevitable to talk about Japanese Lolita fashion, a subculture that emerged in the 1990s and has since developed into an international style. Drawing on Victorian and Rococo aesthetics, Lolita fashion emphasizes modesty, elaborate detail, and doll-like silhouettes. Alice in Wonderland quickly became one of its key references. Blue dresses, pinafores, aprons, and headbands all echo Alice’s iconic imagery, both from Tenniel’s illustrations and Disney’s 1951 animation.

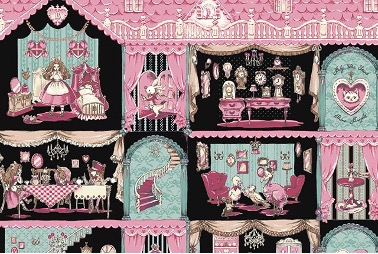

Brands such as Angelic Pretty, Baby, The Stars Shine Bright, and Metamorphose temps de fille have released collections directly inspired by Alice, often incorporating teacups, playing cards, clocks, and rabbit motifs into their prints. Some prints, like Angelic Pretty’s “Alice in Wonderland” series (2010–2015), include tiny illustrations of the Cheshire Cat or the Mad Hatter’s tea party scattered across skirts, creating a wearable narrative that evokes Carroll’s story. These prints are not just decorative; they allow the wearer to physically inhabit a fantastical world, mirroring Alice’s journey through Wonderland.

The Alice influence extends to coordination and styling choices. Lolita wearers often pair knee-high socks with motifs of clocks or teapots, accessorise with miniature teacup handbags, or wear bonnets decorated with playing cards. This level of thematic immersion transforms outfits into storytelling devices, reflecting the narrative structure of Carroll’s work. Harajuku street style photographs often showcase full Alice-inspired coordinates, emphasising whimsy and surreal proportion, oversized bows, tiered skirts, and exaggerated silhouettes echo the dreamlike distortions of Wonderland.

Culturally, Alice-inspired Lolita fashion provides a form of escapism and identity play. Much like Alice, the wearer steps into a world that exists outside the rules of adult society. Scholars have noted that this fashion enables participants to explore agency, creativity, and childhood imagination while resisting societal pressures of adulthood (Kérchy, 2021). In other words, Alice’s presence in Lolita is not merely visual; it is performative, symbolic, and psychologically immersive.

A previously mentioned artist, Nicki Minaj has also drawn on Lolita fashion, blending it into her early public image and brand identity. Her connection to Harajuku and Lolita aesthetics became especially prominent during her Pink Friday (2010) era. Minaj’s playful use of oversized bows, pastel colors, frilly dresses, and wigs brought together childhood imagery and hyper-feminine pop culture, but always with a provocative twist. Videos like “Super Bass” use exaggerated fashion to fuse innocence with sexual confidence, while “Moment 4 Life” dresses her in princess-like gowns that suggest fantasy and transformation. By reworking Lolita aesthetics through the lens of Alice in Wonderland, Minaj redefined femininity as fluid, performative, and bold, reflecting some of the same themes Carroll explored with identity and societal norms.

High fashion has also repeatedly turned to Wonderland for inspiration. Designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen, and Rei Kawakubo have incorporated Carroll’s dreamlike imagery into their collections. An article in Vogue Singapore (2022) highlights how Wonderland’s visual excess emerges in oversized bows, mismatched patterns, asymmetric cuts, and surreal silhouettes, fashion choices that echo Alice’s fluctuating size and the illogic of her dream world.

Alice’s role as a fashion icon, however, predates modern subcultures and designers. According to Susina (2020), early illustrations of Alice helped standardize girls’ clothing in the Victorian era, shaping how young girls were dressed well into the twentieth century (p. 85). The pinafore dress, long associated with innocence and domesticity, became visually tied to Alice and has endured as a costume shorthand ever since. In this way, Alice’s fashion influence began not only on the page but in everyday childhood attire, blending fantasy with lived reality.

Across this three-part exploration, we have seen how Carroll’s playful illogic shaped the original story, how its imagery and characters flourished in music videos and pop culture, and finally, how Wonderland continues to inspire fashion, from Japanese Lolita subcultures to haute couture runways. The thread running through all of this is the way Alice’s dreamworld refuses to stay in one place: it slips between literature, film, music, and design, continually re-emerging as a metaphor for freedom, transformation, and identity. Characters like the Mad Hatter or symbols like the rabbit hole remind us that nonsense can be meaningful, and that imagination itself can be a tool for resistance and reinvention. More than 150 years later, falling with Alice still offers us new ways of seeing the world.

CLICK:

3 posts references:

- Auerbach, N. (1973). Alice and Wonderland: A curious child. Victorian Studies, 17(1), 31–47.

- Bulkeley, K. (2019). The subversive dreams of Alice in Wonderland. International Journal of Dream Research, 12(1), 49–59.

- Carroll, L. (2009). Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1865)

- Hennelly, M. M. (1982). Alice’s Big Sister: Fantasy and the Adolescent Dream. Journal of Popular Culture, 16(1), 72.

- Hutton, R., & Whatman, E. (2018). Music videos and pop music. In P. Greenhill & J. A. Anderson (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Fairy-Tale Cultures (pp. 548–555). Routledge.

- Johannessen, F. H. (2011). Alice in Wonderland: Development of Alice’s identity within adaptations (Master’s thesis, Universitetet i Tromsø).

- Kérchy, A. (2021). The fabulous adventures of Alice with fashion, science, and Pinocchio. Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS), 27(1), 169–178.

- Kim, M. (2018). Literature-based instruction for fashion design class: Using Alice’s Adventures in Wonderlandby Lewis Carroll. Fashion & Textile Research Journal, 20(3), 287–292.

- MacArthur, F. (2004). Embodied Figures of Speech: Problem-Solving in Alice’s Dream of Wonderland. Atlantis, 26(2), 51–62.

- Monden, M. (2022). Transformations: Aimer’s ‘I Beg You’ and Alice in Japanese Music Video. In W. McCarthy (Ed.), Alice in Wonderland in Film and Popular Culture (pp. 255–271). Springer International Publishing.

- Susina, J. (2020). Fashioning Alice: The career of Lewis Carroll’s icon, 1860–1901 by Kiera Vaclavik. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 45(1), 84–87.

- Thomas, R. R. (1988). Profitable dreams in the marketplace of desire: Alice in Wonderland, A Christmas Carol, and The Interpretation of Dreams. Nineteenth Century Contexts, 12(1), 35–45.

- Vizcaíno-Verdú, A., Aguaded, I., & Contreras-Pulido, P. (2021). Understanding transmedia music on YouTube through Disney storytelling. Sustainability, 13(7), 3667.

- Vogue Singapore. (2022). Alice in Wonderland: A fashion legacy. https://vogue.sg/alice-in-wonderland-fashion/