The discourse around globalization and the transmission of subcultures has mostly focused on how Western culture spreads into “other” cultures and how those cultures adapt such subcultures within their own histories and contexts. However, this essay aims to explore a different direction of cultural transmission: from Japan to Thailand, analyzing the spread and transformation of the BL subgenre.

The essay is divided into two main sections: the Japanese BL space, and the Thai BL scene. The first section discusses the historical context of homosexuality in Japan, the creation of the BL genre, and the conflicts and achievements within it. The second section examines the history of homosexuality in Thailand, the transmission of BL, its development and hybridity, insider criticism, and finally the influence of Thailand on the current state of BL in Asia.

JAPAN’S YAOI

The term nanshoku, referring to male homosexuality in pre-Meiji Japan, derives directly from the Chinese word nanse. It was believed by the Japanese that homosexuality had been an imported practice from mainland China. However, as Leupp (1997) discusses, Japan did not view the nanshoku code as a negative import but rather as a ‘teaching or way’ imbued with positive masculine connotations. This nanshoku practice was primarily pederastic, involving younger partners who were adolescents or prepubescents, in a mentor-mentee relationship. With the beginning of the Meiji era, views on homosexuality remained largely unchanged.

However, as Japan pursued westernization, it introduced various societal changes, including a sodomy ordinance in 1872 under the Ministry of Justice, which punished homosexual acts based on the Keikan code of homosexual perversion. After the Russo-Japanese War (1904), nanshoku practices declined, partially because the assault and recruitment of bishonen (beautiful young men) by gangs of young male students raised public concern.

These acts worsened the public perception of homosexuality, which newspapers described as ‘horrible depravity,’ fueling a successful anti-sodomy campaign aimed at stopping such behavior. While this campaign reduced vandalism, it failed to criminalize homosexuality in the public mind. Makoto (1994) describes a renaissance of the kagema (male prostitutes) in the 1920s, a revival met with public disapproval.

Homosexuality was increasingly seen as an indecent and unnatural deviance, especially after the Hentai Seiyoku Code established the understanding of homosexuality as a sickness in Japanese society, a stigma that persists today.

Amidst this societal animosity and later the AIDS pandemic, a new subgenre of manga known as bishonen manga emerged in the 1970s, influenced by the boom of shojo manga (targeted at young girls). These comics featured androgynous male characters whose protagonists represented an ‘idealized self-image’ for girls, belonging to a ‘third sex’ (Chizuko, 1998). Mori Mari’s Koibitotachi no mori (1961) is often credited as the starting point of the Yaoi genre.

The term yaoi itself originated in the 1980s as an acronym for “no climax” (yama nashi), “no punch line” (ochinashi), and “no meaning” (imi nashi), describing pornographic parodies with poor storytelling originally applied to fan works (Mizoguchi, 2003). Unlike bishonen manga, yaoi emphasized two visible male characters in love, without androgyny.

The genre grew in popularity during the early 1990s, but the term yaoi eventually fell out of favor as it was considered derogatory toward the predominantly female creators, who mainly engaged in unpaid DIY fan art without formal literary training. Instead, the label BL or boizu rabu was adopted (Mizoguchi, 2003).

Using Haenfler’s (2014) definition of subculture as a “diffuse social network having a shared identity, distinctive meanings around certain ideas, practices, and objects, and a sense of marginalization from or resistance to a perceived ‘conventional’ society” (p.16), the BL subgenre fits within Japanese subculture due to homosexuality’s complicated public image. Interest in homosexuality runs counter to Japan’s dominant heterosexual hegemony, yet BL was not created as resistance to this culture. Instead, Papineau’s reinterpretation of ‘third space’ better captures the dynamic:

“…they represent something beyond the standard binary scheme of ‘mainstream/underground’ popular in cultural studies. The idea of a third space… allows for a more nuanced dynamic of agency that does not reduce to discourses of passive consumption nor of counter-hegemonic resistance.” (Papineau, 2021, p.50)

Radway’s (1991) study in Reading the Romance highlights how romance novels, despite reinforcing patriarchal ideals, fulfill escapist desires for female readers. Similarly, Japanese BL fans, known as fujoshi (“rotten girls”), developed the genre not to oppose Japan’s homophobic attitudes, but as an escape from dissatisfaction with shojo anime written by men (Mizoguchi, 2003). By erasing female characters, the genre avoids negative relatability for women. However, this female-authored genre paradoxically reinforces heterosexual tropes, such as:

- Rape as an expression of love;

- Protagonists claiming to be straight despite homosexual involvement;

- Sex roles corresponding rigidly to masculine/feminine appearances;

- Never reversing these roles;

- Sex always involving anal intercourse (Mizoguchi, 2003).

The lack of lived experience and disinterest in realistic representation among female writers has resulted in problematic tropes and interpretations of love between men.

THAILAND’S BL

Thailand’s history with homosexuality is marked by misconceptions. Jackson (1999) points out that tourists mistake the abundance of gay bars, queer TV characters, and public displays of affection as indicators of social acceptance. While Thailand is known for its higher number of transsexual and transgender individuals, negative social attitudes persist. Transgender males are disparagingly called “plastic flowers,” and transsexual males “second-class ladies,” implying inferiority and unnaturalness (Numun, 2012). This silent negativity coexists with a public neutrality influenced heavily by Buddhism.

Thai cultural beliefs in reincarnation and karma teach that being born homosexual is punishment for bad karma in past lives. However, Buddhism also emphasizes mercy and pardon, which explains Thailand’s appearance as an open society characterized by kindness and non-judgment. While Thailand has no history of anti-homosexual laws or public outrage, marital rights remain absent, and social reputation is prioritized. Wijngaarden observes:

“This culture fosters people’s abilities to find their identity in their group […] a social game that emphasizes outward appearances that are not compensated by inner development.” (Lind van Wijngaarden, 2021, p.22)

This passive societal attitude has laid the groundwork for BL culture to become a form of soft power for Thailand. Unlike Japan, where BL remained subcultural, BL in Thailand entered mainstream media and grew into a vibrant scene. Following Bennet’s (2004) concept of a “scene,” which accounts for fluid, interchangeable identities rather than deviance from a single dominant culture, BL media reached Thailand through manga in the 2000s.

Like Japan, early Thai BL was written by anonymous female fans sharing online fan fiction of male idol fantasies, mainly Kpop and Jpop. The term Fujoshi found a Thai equivalent in “Sao Y,” combining Sao (sister) and Y (boy’s love).

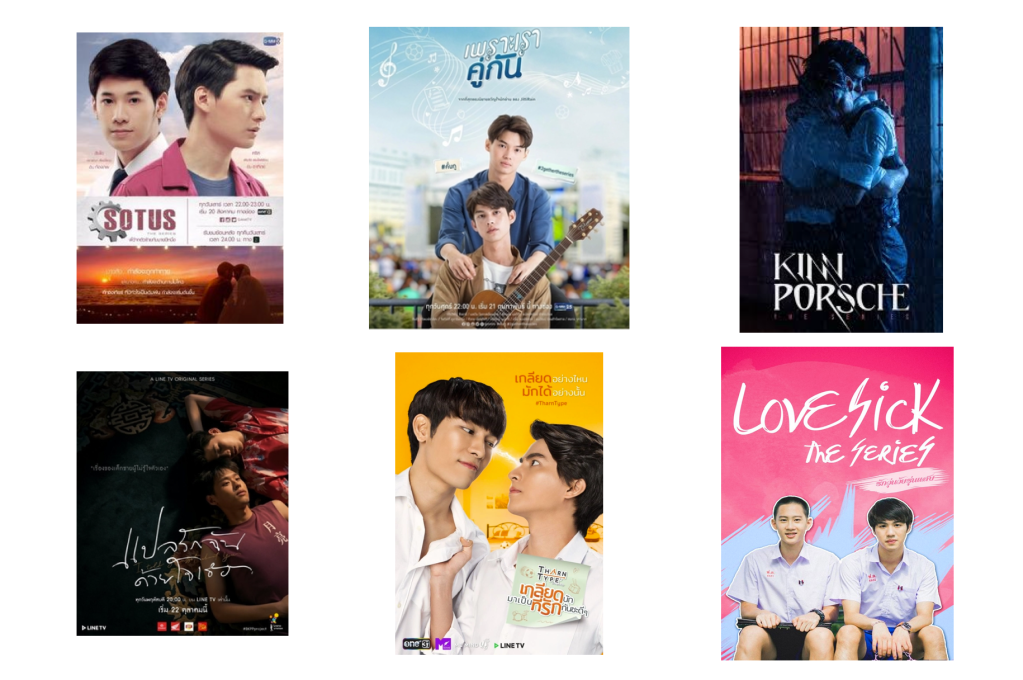

Lovesick: The Chaotic Lives of Blue Short Boys by Latika Chumpoo is credited as the first BL manga to achieve wide popularity in Thailand. It was adapted into a series by GMMTV in 2014, marking the first BL manga adaptation in Thailand (Baudinette, 2019).

Prior to this, mainstream hints appeared in shows like Hormones (2013), which included a gay couple, and the film The Love of Siam (2007), addressing gay youth struggles. However, these works did not captivate Thai audiences like Love Sick did. The 2016 GMMTV series Sotus became Thailand’s first international BL hit and solidified the genre’s formula. Garcia’s (2005) concept of hybridity, a sociocultural process combining separate structures to create new forms, applies here: Thai BL fused problematic Japanese tropes with characteristics of Thai lakorn (melodrama).

Over time, the genre expanded to include fanservice and marketing tactics borrowed from anime and K-pop, such as merchandise, concerts, fan meetings, and live streams, strengthening parasocial relationships between actors and fans, but through film rather than music. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the growth of Thai BL. GMMTV’s 2Gether (2020) became the most-watched BL show, with 8 million views in two weeks, benefiting from easy access on YouTube during quarantine. This wide accessibility helped Thai BL surpass the reach of its Japanese predecessors.

A key difference between Thailand’s BL and Japan’s is the inclusion of political themes. Early BL in both countries avoided political discussion, as homosexuality was not openly discussed or recognized (Hori, 2013). However, from 2021, Thai BL evolved from a female-oriented subgenre into a more openly queer scene.

GMMTV’s recent shows incorporate themes such as marriage equality, polyamory, transsexuality (in a serious, non-comedic way), and disability alongside queerness (3 Will Be Free, 2019; Last Twilight, 2023). Shows like I Told Sunset About You (2020) and Not Me(2021) engage directly with LGBTQIA+ political discourse, achieving mainstream success while maintaining the BL label. Thai BL’s global rise echoes Garcia’s (2004) observation that globalization stimulates differential reactions.

Thailand’s BL scene now faces a divide similar to Japan’s 1990s yaoi labeling controversy. Alice Oseman, author of Heartstopper(2022), distanced her work from BL and yaoi due to their fetishization of queer men. Yet Heartstopper and GMMTV’s My School President (2023) are essentially the same genre, high school male romance, differing only by label and origin. This tension divides audiences between presumed straight female fans (fujoshi or Sao Y) and queer viewers, with some calling for non-labeling based on characters’ sexuality (Hori, 2013).

The impact of Thai BL has inspired other Asian countries to produce similar content, even influencing Japan, which saw a BL show production boom between 2019 and 2023. The Philippines began BL productions in 2020 (GameBoy, Hello Stranger), Taiwan started HIStory in 2017, and South Korea debuted Where Your Eyes Linger in 2021. As of 2023, these four countries lead Asian BL production, with Thailand still at the forefront. The Department of International Trade Promotion estimated Thai BL’s revenue at 360 million baht in 2023 from business matching alone.

In summary, while Japan and Thailand have both historically held negative social and political attitudes toward male homosexuality, the transmission of BL to Thailand produced significantly different outcomes. Japanese BL remained niche, limited by a female audience focus and persistent homophobia, and alienated queer communities. Thailand, influenced by Buddhism and utilizing film as a medium, broadened BL’s reach by converting its audience and humanizing queer characters. This expansion created a scene united by shared identity around a mediatic subgenre. Thailand’s success not only mainstreamed BL domestically but also influenced other Asian countries, illustrating a case where the overseas adaptation surpasses the original cultural source.

REFERENCE LIST:

- Baudinette T. (2019) Lovesick, The Series: adapting Japanese ‘Boys Love’ to Thailand and the creation of a new genre of queer media, South East Asia Research, Vol.27 Issue 2, pp. 115-132.

- Bennett, A. & Peterson, R (2004) (Eds) Music Scenes: Local, Translocal, Virtual. Nashville: Vanderbuilt.

- Chizuko U. (1998) Hatsujo sochi: erosu no shinario (The mechanism of excitement: erotic scenarios). Tokyo: Chikuma shobo.

- DITP (2023) First Business Matching for Boys’ Love Series Is Big Hit Available at: https://www.ditpthinkthailand.com/first-business-matching-for-boys-love-series-is-big-hit/ (Accessed 10 February 2024)

- García C, N. (2001 [1995]). Culturas híbridas. Buenos Aires: Paidós

- Haenfler, R (2014). ‘What is a Subculture’ in Subculture: The Basics. London: Routledge.

- Hodkinson, P. (2011) Media, Culture and Society: An Introduction. London: Sage. Chapter Two, ‘Media Technologies.’ pp.35-59

- Hori, A. (2013) On the response (or lack thereof) of Japanese fans to criticism that yaoi is antigay discrimination. Symposium, Vol.12. Kyoto Japan. TWC Editor.

- Jackson P. A. & Sullivan G. (1999). Lady boys tom boys rent boys: male and female homosexualities in contemporary Thailand. Harrington Park Press.

- Leupp G.P. (1997) Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. California: University of California Press.

- Lind van Wijngaarden J. W. (2021) Male Homosexuality in 21st-Century Thailand. A Longitudinal Study of Young, Rural, Same-Sex-Attracted Men Coming of Age. Anthem Press.

- Makoto, F., & Lockyer, A. (1994). The Changing Nature of Sexuality: The Three Codes Framing Homosexuality in Modern Japan. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, vol. 7, pp. 98–127.

- McLuhan, M. (2001) Understanding Media. London: Routledge (originally published 1964).

- Mizoguchi, A. (2003). Male-Male Romance by and for Women in Japan: A History and the Subgenres of “Yaoi” Fictions. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, vol. 25, pp.49–75.

- Numun, W. (2012). Significance of Homosexuality in Thai Society. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Prince of Songkla University, vol. 8 (2), pp. 157–170. Available at https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/eJHUSO/article/view/85753. (Accessed 5 February 2024)

- Papineau E. I. (2021) ‘RE-THINKING PUNK DISCOURSE AND PURPOSE: A CASE STUDY 37 OF MUSLIM PUNK IN JAVA’ in Bestley R. et all., TRANS-GLOBAL PUNK SCENES: FURTHER REFLECTIONS. Bristol: Intellect, pp. 50.

- RADWAY, J. A. (1991). Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- Thompson, J. B. (1995), The Media and Modernity, Cambridge: Polity Press