My mom was a housekeeper. I grew up with a mother who spent half her life looking after other people’s children. I remember her coming home with horror stories about how the kids treated her that day, or how a new child she looked after told her he loved her more than his own mom. The first time I watched The Help, I couldn’t help but relate deeply to the plot, especially the scene between the white protagonist’s childhood nanny and her biological mother.

Because art always reflects reality, and as cinematic as it sounds, I’ve been in the position of witnessing my mother’s dignity and human decency crushed in front of me by her boss. One day, she was late coming back from her break because she had to pick me up from the airport. My mom was naive enough to believe she had a good relationship with her boss, but that day she realized all it took was being five minutes late to be humiliated in front of her 10-year-old daughter.

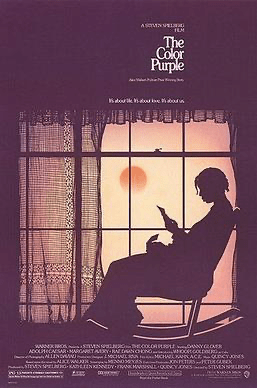

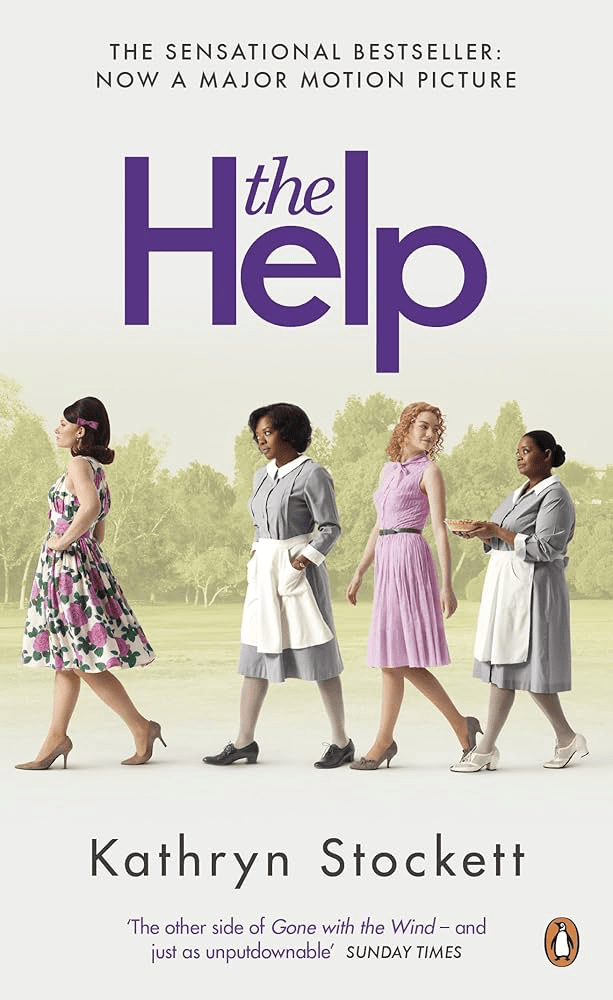

Black womanhood is layered and complex, I could write hundreds of essays on it. But for now, I’ll start with the last two films I’ve watched. Lately, I’ve been binge-watching classic movies I’d never had the chance to experience until now. In this piece, I want to reflect on how this complexity is portrayed in two films , The Color Purple (1985) and The Help(2011). Though made decades apart, both stories center Black women’s experiences and highlight the forces that attempt to define and contain them.

This discussion unfolds in three parts: an individual analysis of each film, a comparison between them, and a final reflection on the identities their characters represent.

The Color Purple: Love, Survival, and Silenced Queerness

Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple, adapted from Alice Walker’s 1982 novel, follows Celie, a Black woman in early 20th century Georgia, as she survives decades of abuse, neglect, and oppression. Played by Whoopi Goldberg, Celie is subjected to sexual violence by her father, forced marriage, child loss, and emotional isolation. Her reality is one where both gender and race are used to strip her of agency.

Dialogues like:

“The Olinka don’t believe in educating girls, they are like white people at home who don’t want Black people to learn,”

or

“Look at you, you are Black, you are poor, you are ugly, you are a woman, you are nothing at all,”

directly underline the film’s message: that Black women face a unique, compounded oppression at the intersection of racism and sexism.

But while the film explores Celie’s suffering, it also traces her path toward self-love and emotional intimacy, particularly through her relationship with Shug Avery. The queerness of Celie’s character, clear in the novel, is less explicit in the film, a limitation likely shaped by 1980s mainstream cinema, but it’s still present.

A quiet kiss between Celie and Shug, and the line “Purple cause she wanted to be loved,” spoken as they walk through a field of flowers, gestures at the film’s second message: Black women are denied love, both romantic and self-directed, by a world that tells them they don’t deserve it. The film portrays Black men largely as antagonists. Celie’s husband Albert is one of many who enact patriarchal violence. Yet The Color Purple resists drawing a simple gender binary.

Miss Millie, a white mayor’s wife, becomes a villain in her own right when she punishes Sofia, a Black woman who refuses to work for her, with incarceration. Power, the film suggests, can be cruel in many forms, and white womanhood is not inherently innocent.

The Help: The Whiteness of Empathy

Tate Taylor’s The Help (2011), based on Kathryn Stockett’s novel, tells a different but equally complex story. Set during the civil rights era, it follows Skeeter — a young white writer, as she interviews Black maids in Jackson, Mississippi, hoping to document their experiences.

The narrative centers Aibileen (Viola Davis), a housekeeper who has raised 17 white children while grieving her own son’s unjust death. Her story, and those of other maids, is framed through Skeeter’s perspective, a storytelling choice that immediately sparked critique.

As the British Film Institute pointed out in 2011, the film functions as a “clandestine project documenting the experiences of the town’s African American maids.” Yet, it’s also a project that benefits its white author and protagonist more than the subjects it supposedly centers. The critique deepens when we consider that Kathryn Stockett, like her character Skeeter, profits from Black stories without living them.

“Like Dolezal,” one article argued, “both Stockett and Skeeter rely on their invisible whiteness to inhabit, and appropriate from, marginalized women’s subjectivities.” Skeeter functions as a white savior figure, though, interestingly, she doesn’t actually save anyone. She achieves her publishing dream, while the futures of Aibileen and the others are left ambiguous. By contrast, Octavia Spencer’s character Minny, a fellow maid, reminds us where real solidarity lies:

“I’m gonna take care of Aibileen, and she’s gonna take care of me.”

In the end, Black women are left caring for each other, not because they want to, but because no one else will. One of the film’s most powerful moments is a question Skeeter asks:

“How does it feel to raise a white child while yours is at home?”

It’s a question that cuts across history, geography, and culture, and leads us into our final reflection.

Intersection and Parallel Lives

Despite the time gap between the stories, characters across The Color Purple and The Help mirror each other. Skeeter, for instance, can be compared to Sofia from The Color Purple in terms of gender performance. While their races differ, both face criticism for not conforming to “womanly” expectations. Yet only one of them, Sofia, also suffers racialized violence, incarceration, and domestic abuse.

Misogynoir, the term coined to describe the specific intersection of racism and sexism Black women face, is vividly present in both stories. In The Help, Minny endures abuse from her Black male partner while also facing workplace discrimination from her white boss, who won’t let her use the toilet because she fears “Black diseases.” Similarly, The Color Purple shows Celie encouraging Sofia’s husband to beat her into submission, a moment that reveals how even victims of patriarchy can perpetuate it.

That same contradiction appears in The Help through Skeeter’s mother, who fires the maid that raised her out of fear of white social judgment. Characters like Miss Millie (The Color Purple) or Skeeter’s mother (The Help) embody a white femininity that wields its power against Black women, even while claiming to be delicate or oppressed themselves.

Finally, both films underscore how Black women are systematically denied motherhood. In The Color Purple, Celie’s children are taken from her at birth. Sofia is imprisoned and separated from her children. In The Help, Aibileen and Minny spend their lives raising white children while their own families are left behind.

They must choose between survival and presence, often sacrificing one to secure the other. These films remind us that the intersection of Blackness, womanhood, and labor is not just painful, it’s political. And while neither film is perfect, one flattens queerness, the other centers whiteness, both invite us to look deeper into how stories are told, who tells them, and who gets left behind.

Because at the end of the day, Black women have always been writing, surviving, resisting, and raising more than just children.

Adding a much personal opinion, I disliked both movies, but could also find a great case study on both.

REFERENCE:

- Thouaille, M-A. (2015) “Nice white ladies don’t go around barefoot”: racing the white subjects of The Help (Tate Taylor, 2011), Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 10, pp. 96–112. Accessed from: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.10.06.

- Wren, R. B. A. M. (1996). RERUNNING `THE COLOR PURPLE’ CONTROVERSY OVER 1985 MOVIE NOW SEEMS UNFATHOMABLE, Five Star Edition, St. Louis Post – Dispatch, Accessed from: https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/rerunning-color-purple-controversy-over-1985/docview/305151108/se-2

- Bobo, J. (1989). Sifting Through the Controversy: Reading the Color Purple. Callaloo, 39, 332–342. Accessed from: https://doi.org/10.2307/2931568

- Jerald, L. et al. (2016) Subordinates, Sex Objects, or Sapphires? Investigating Contributions of Media Use to Black Students’ Femininity Ideologies and Stereotypes About Black Woman, Journal of Black Psychology 43:6, 608-635, Accessed from: https://journals.sagepub.com/.

- Bailey, M. (2021) Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance, New York, USA: New York University Press. Accessed from: https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479803392.001.0001

- Walker, A. (1982) The Color Purple, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

- Stockett, K. (2009) The Help, Penguin Books, London.